The winner takes it all

Fat tails, positive feedback loops, Pareto Principle, black swans, and more

Imagine waking up on a perfectly normal day:

Before heading to work, you take your daily prescription medication. You get stuck in traffic on your commute. At the office, you handle an escalation about an important customer. After lunch, while preparing for performance reviews, you wonder why more of your employees can’t be like your star performer. On your drive home, you catch up with a good friend. Before bed, you unwind with a book by your favorite author.

I’m sure your day looks a little different, but our ordinary days are by no means “normal.” Every event in that day was shaped by fat-tailed, winner-take-all processes. And mistaking these extreme environments for normal ones can cost you dearly.

ABBA said it best: “The winner takes it all.”1

Thin tails vs. fat tails

The normal distribution is well-known and useful for many things… but terrible for many others. Unfortunately, we often apply it universally, even where it doesn’t belong.

The normal distribution belongs to the “thin-tailed” class of distributions. This means that extreme events (events in the tails) are exceedingly rare. This is in contrast with “fat-tailed” distributions where extreme events, while still uncommon, occur far more regularly.

At first glance, the distinction might seem trivial, but the tails make all the difference. The capacity for extreme events is why we have winner-take-all environments. All the action lives in the tails.

Yet people tend to miss the signs — like positive feedback loops, asymmetric payoffs, and compounding returns — and mistake fat-tailed environments for thin-tailed ones. This means overexposure to catastrophic risk, and missed opportunities for massive upside.

Let’s revisit the events from that “normal” day to bring these fat tails to life:

… daily prescription medication…

Pharma R&D is a classic fat-tailed environment. Most drug candidates never get approved, and of those that do, a small minority make up the vast majority of pharmaceutical revenue.

This dynamic shows up with “blockbusters,” an industry term for drugs that exceed $1 billion in revenue in a given year2:

This winner-take-all environment is due to factors like:

Asymmetric payoffs: Failed drugs have capped losses (R&D expenses) but successful drugs have uncapped upside (billions in revenue)

Regulation and limited development capacity: Only top candidates get resources3

Positive feedback loops: Successful new drugs influence guidelines, clinician education, and reimbursements

Many other investments like venture capital and options trading share this fat-tailed, winner-take-all nature. Most have weak returns, but the winners can make it all worth it.

… traffic…

Traffic is another fat-tailed environment. Most trips are predictable, but some completely blow up the forecast. This happens because of:

Asymmetric constraints: Speed limits mean trips can’t be significantly faster, but they can be much longer

Extreme inputs: Rush hour, crashes, severe weather, and other shocks are not uncommon and can have a significant impact on traffic

Compounding: The longer the initial blockage, the more traffic builds up, the longer it takes to clear the roadway

Project delays follow the same pattern. Have you ever seen a large project completed significantly ahead of schedule? The more a project is delayed, the more opportunities there are for external factors to affect timelines. And surprises almost always affect timelines in the same direction — longer.

… an important customer…

The ‘80/20 rule’ (AKA the Pareto Principle) is sometimes used to describe the worth of customers: “80% of profits come from 20% of customers.” Real-world ratios vary but the concept holds: Most customers aren’t that valuable, and some are extremely valuable4.

The nature of customer churn is a primary reason for this: New customers are far more likely to churn than tenured ones. Maybe they realized that they didn’t need the product or service, or faced a painful gap between expectations and reality, or simply had a one-time need. But as time goes on, the likelihood that these factors will cause them to churn decreases.

The longer they stay, the longer they are likely to stay.

This often makes your most valuable customers far more valuable than you think and the bulk of your customers less valuable than you think. It also means that your “average customer” doesn’t really exist.

… your star performer…

It’s often said that the best programmers are 10x more productive than their peers. This is a fat-tailed distribution at work. While the magnitude varies in practice, employee productivity is generally better explained by a fat tail than a thin one (e.g. normal distribution).

Just imagine losing your best employee. Does it hurt 50% more than losing an average employee? Or does feel more like 5x?

According to my analysis of the BLS data5, the top 10% of employees are generally 3-4x as productive as “average” employees. I think this is primarily because of:

Positive feedback loops: High performers earn more trust, autonomy, visibility, and resources, contributing to further high performance

Multiplicative effects: If productivity = Effort x Skill x Luck (or something along these lines), tails will be fatter than if these components were simply added together

Role heterogeneity: Some tasks and roles have inherently more potential impact

… a good friend…

Near the end of our “normal” day, we chatted with a good friend. Relationships, too, have fat-tailed, winner-take-all dynamics.

For example, some people are far more connected than others. We allocate time disproportionately across our relationships. And while most relationships have a minimal impact on our lives, some have an extreme impact.

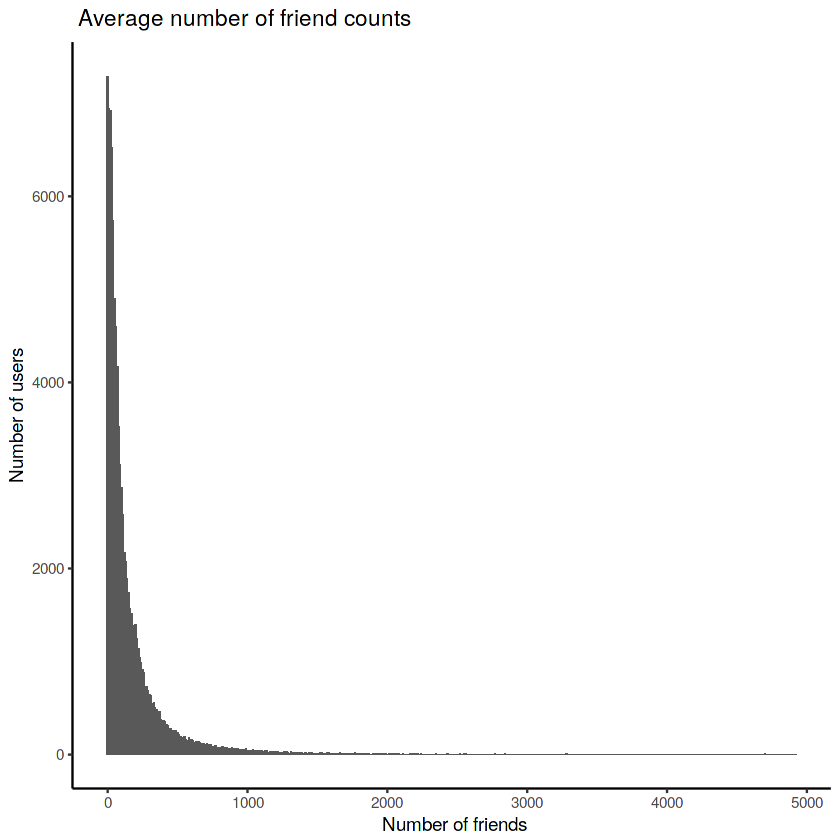

The following analysis of facebook friend counts6 shows the fat-tailed nature of individual connectedness. While most users in the dataset have fewer than 100 friends, some have thousands:

This may be driven by a positive feedback loop: The more connections you have, the more second degree connections you have, who are more likely to turn into first degree connections. There may also be a preference to be connected with those who are more connected.

Wealth distribution is similar. Compounding returns mean that capital generates more capital, widening the gap between the extremely wealthy and everyone else. And as someone becomes wealthier, they often gain preferential access to investment opportunities, networks, and advice.

… a book by your favorite author…

Book sales are another winner-take-all environment. There is a good chance millions of people share your favorite author. Most published books sell less than a thousand copies, while a small fraction sell millions7.

This extreme concentration applies to other types of “share” as well — market share, share of wallet, share of attention, etc. For example, ChatGPT captures the lion’s share of site traffic among its competitors:

Positive feedback loops contribute to this winner-take-all pattern. Buying a product increases your familiarity with the product, increasing your likelihood of purchasing again. Using a product often increases the awareness others have of the product. And companies that make more money can invest more into innovation and availability.

Share capture often follows a predictable pattern8. Your slice of the pie is a function of 1. the number of viable alternatives to your product or service, and 2. how your offering ranks among them. This means you have two levers to pull to increase share — take alternatives off the table, or increase preference for your offering.

Conclusion

Fat-tailed, winner-take-all environments are everywhere. And failing to recognize them can be disastrous. In The Black Swan, Nassim Taleb writes:

“Almost everything studied about social life focuses on the “normal,” particularly with “bell curve” methods of inference that tell you close to nothing. Why? Because the bell curve ignores large deviations, cannot handle them, yet makes us confident that we have tamed uncertainty.”

That overconfidence is something we can address. Consider the following suggestions:

Get good at identifying fat-tailed environments. These environments often share certain traits; positive feedback loops, asymmetric structures, constraints, multiplicative processes, and extreme inputs. If you feel inclined to assume something is “normal,” keep an eye out for these attributes. If you still aren’t sure, ask your favorite LLM.

Get fat tails to work for you, not against you. This might mean investing in relationships outside of your core group to increase exposure to new opportunities. Or taking the investment with long odds but massive upside. Or recalibrating your expectations on when that large project will really be done. Or doubling down on your most valuable customers.

And if nothing else, just remember: ABBA was right.

Peter Thiel gets an honorable mention for: “We don’t live in a normal world, we live under a power law.” A power law is one of the better-known types of fat-tailed distributions.

2-3% of drugs that are formally investigated make it to market (17,524 Investigational New Drug receipts from 2014 to 2023, 456 approvals granted)

The work of Dan McCarthy and Pete Fader on this topic has been enlightening to me and many others. I can’t recommend their work enough. A good place to start might be this article or this book.

Link to BLS dataset. Chart based on the average dispersion statistics from 2017-2021 across industries. Converted log-difference into normal units and fit a distribution consistent with the data.