Connecting CX and business value

Common misconceptions about the relationship between the two, with practical tips on where to focus

Through the course of my work, I have been asked variations of the following question hundreds of times:

What is the dollar value of a point in NPS?1

I can see the allure. It would make it so easy to communicate the value of CX.

But it’s the wrong question.

Why is it the wrong question?

CX teams don’t create business value by increasing customer satisfaction. They create business value by driving change that increases cash flow. This means improving customer acquisition, spend, retention, or cost to serve.

While CX scores can be a great way to represent value created for customers, they are not a reliable proxy for these business outcomes. If you disagree with this distinction or if it seems trivial to you, read on! If you’re already convinced, you can jump ahead to the section “What do we do instead?”

Reason #1: Customer satisfaction and business value often move in opposite directions

Consider the following story:

The CX team at Company ABC proposes the company start an NPS program. They cite research that says NPS leaders grow faster and are more profitable. The CFO likes this and approves the investment. The CX team gets to work and begins reporting NPS gains, welcomed by applause and high fives.

Some years later, in the middle of one of these NPS celebrations, the CFO shouts:

“I’m sick of it! You’ve been celebrating these NPS gains for years. You said this would bring revenue growth and profitability, but over the same time period our revenue growth and profitability have underperformed our competitors. What's going on??”

Before reading ahead, what would you do if you were on that CX team?

You may need to reset expectations as to how your program creates business value. Consider whether any of the following might have happened:

Your least satisfied customers are leaving, raising your average CX score and decreasing revenue.

Your customer satisfaction improvements are achieved through some form of discounting.

You are providing low value customers with white glove service, increasing scores and decreasing margin.

You are improving memorable experiences, but not ones that affect the desired customer behavior.

Your competition is improving experiences faster and/or better so your CX investments didn’t result in sufficient differentiation over alternatives.

Your customers’ actual behavior differs from their self-reported loyalty.

Macroeconomic and demographic trends are influencing customer preferences and behavior.

CX scores are being gamed and don’t represent genuine improvements.

Your recently acquired customers are fundamentally different from your legacy customers in terms of expectations, behaviors, personality, etc.

All this to say that there are a lot of reasons for CX scores and business value to move in opposite directions.

Reason #2: Treating satisfaction as a proxy for business value incentivizes the wrong behavior

Organizations often need to make decisions based on imperfect data. So what’s the harm in treating customer satisfaction (which, all else equal, is a good thing) as a proxy for business value?2

Let’s look at a few scenarios and imagine how this might affect decisions:

Customers are unhappy with customer support

If the company uses satisfaction as a proxy for business value, it might over-invest in addressing the reasons customers aren't satisfied with support. A better approach would be to optimize the level of support based on the impact on customer behavior.

Customers are spending a lot with competitors

If the company uses satisfaction as a proxy for business value, it might over-invest in making customers happier. A better approach would be to figure out why certain customers use competitors and determine which reasons are worth addressing.

Customers are leaving at an increasing rate

If the company uses satisfaction as a proxy for business value, it might focus on the issues cited by dissatisfied customers. A better approach would be to identify the sources of customer churn3 and determine which are worth addressing.

Not getting enough customers from word of mouth

If the company uses satisfaction as a proxy for business value, it might focus exclusively on increasing NPS. A better approach would be to understand which customers actually refer others, why they do or don’t, and what is worth doing about it.

Not seeing a positive correlation between customer satisfaction and behavior

In this scenario, the company might collect more data and analyze it in different ways until they find the association they want to see. A better approach would be to focus on whether their actions are resulting in the desired changes in customer behavior.

Reason #3: Business impact is a question of causation, not correlation

Many companies have made significant investments in CX and, naturally, want to understand their return on investment. This has led many researchers and analysts down the path of connecting customer satisfaction and business outcomes.

While not always the intent, the results of this research are often used to make claims like, “We improved satisfaction by x%, therefore we drove $y in revenue.” Below are 3 widely-used approaches and why they fail to support such claims.

1. Average satisfaction scores and company performance

This research examines the relationship between average satisfaction scores and company performance metrics like stock price, revenue growth, or profit margins. It sometimes shows that companies with higher satisfaction scores perform better4, which allows for statements like “Companies that lead in satisfaction outperform their peers in XYZ metric.”

Conducting or acquiring this research can be a low cost way to inspire others to explore CX-related investments. However, it doesn’t tell us what is causing the superior performance and the results are highly sensitive to the companies, time period, and performance metrics used.

2. Individual satisfaction scores and intended behavior

This research examines the relationship between individual satisfaction scores and intended behavior (e.g. intent to buy again). It often shows that customers with higher satisfaction are more likely to say they will exhibit positive behaviors5, which allows for statements like “More satisfied customers are more likely to say they will…”

This research can also be relatively inexpensive to conduct or acquire and provides a customer-level view, which is preferable to only a company-level view. However, intended behavior often differs from actual behavior6 and asking about satisfaction and intentions in the same survey inflates the strength of the relationship7.

3. Individual satisfaction scores and actual behavior

This research examines the relationship between satisfaction and actual behavior at the customer level. It sometimes shows that more satisfied customers exhibit more favorable behavior (e.g. higher spend, lower churn, lower cost to serve)8, which allows for statements like, “More satisfied customers are more likely to…”

This approach requires greater access to data and analysis resources but provides a better indicator of the relationship between satisfaction and behavior. However, correlation does not mean causation. Satisfaction and behavior can be associated due to other factors, such as customer personality, cognitive biases and heuristics, or reverse causation (i.e. behavior → satisfaction).

The three approaches outlined above can be useful for generating insights, prioritizing investment opportunities, and inspiring others to consider the value of CX. But to make a defensible claim that your CX initiative caused an improvement to a business metric, you often need to go further than association.

What should we do instead?

First, you should know that I deeply believe in the power of experiences. Customer experiences regularly influence my decisions on whether to cancel, upgrade, tell others about a company, and more. And I have seen companies create significant business value with a thoughtful approach to customer experience management9.

But CX just doesn’t translate into business value in the way many people think.

The late Albert Hirschman wrote, “A model is never defeated by facts, however damaging, but only by another model.10” In that spirit, below are 3 recommendations for connecting CX and business value.

Recommendation #1: Use business value metrics to prioritize efforts

CX programs typically focus on customer experience metrics like CSAT, NPS, social media ratings, and average wait time. These are great ways to measure value created for customers. What is often missing, however, are metrics that show value created for the business (i.e. cash flow).

Customer Lifetime Value (CLV) is highly relevant for CX programs and a fundamental driver of business value11. Let’s look at some metrics that contribute to CLV:

Customer acquisition metrics: Sales win rate, cart abandonment rate, # of referrals made per customer, customer acquisition cost (CAC), etc.

Customer spend metrics: Purchase frequency, average order size, average contract value, share of wallet, cross-sell rate, etc.

Customer retention metrics: Customer churn rate, save rate, repurchase rate, etc.

Cost to serve metrics: Problem incidence rate, self service adoption rate, contact resolution rate, average handling time, etc.

While the specific metrics vary by industry, the categories (acquisition, spend, etc.) tend to persist across industries.

As you decide which metrics to focus on, consider the following recommendations:

3-5 metrics. While your program can likely influence more, focus on showing a defensible impact on a small number of highly relevant metrics.

Mix of customer value and business value metrics. Identify win/win opportunities and where there may be tension between value for customers and value for the business12.

Specific to industry and business model. If leaders in your organization don’t recognize your metrics, you may want to align with your company’s metrics13.

Existing metrics. If the data doesn’t exist for the ideal metric, advocate for your organization to start measuring it or to make it available. In the meantime, use the best available metrics.

Based on possible actions. Don’t include metrics that your program can’t influence. Start with the problem you are trying to solve and the actions you can realistically drive. As your program’s focus and ability to drive action changes, your metrics should adapt accordingly.

Recommendation #2: Focus on actions

When someone asks me how much value their CX program has created, I respond by asking what actions it has driven. These conversations often reveal that:

Insights are being shared without visibility into what actions are being taken

Resource requests to act on insights are being denied

No effort is being made to measure the impact of actions on business metrics

These issues result in low value creation (no action = no value) and hard-to-defend claims of value. To avoid them, focus on actions:

To do this, you need to be driving action and you need to know where action is happening. Fortunately, it isn’t necessary to quantify the impact of every action — in fact, it’s probably not worth it. You do, however, need to do this for some actions, especially those that required significant support and resources.

To understand and quantify the impact of an action, use this framework14:

We also need to clarify what constitutes an action. While "launching a new survey" can be a useful program activity, it’s not what we’re looking for. What insights did the new survey generate? What actions did those insights lead to? Keep pulling the thread until you can identify a real change to the customer experience15.

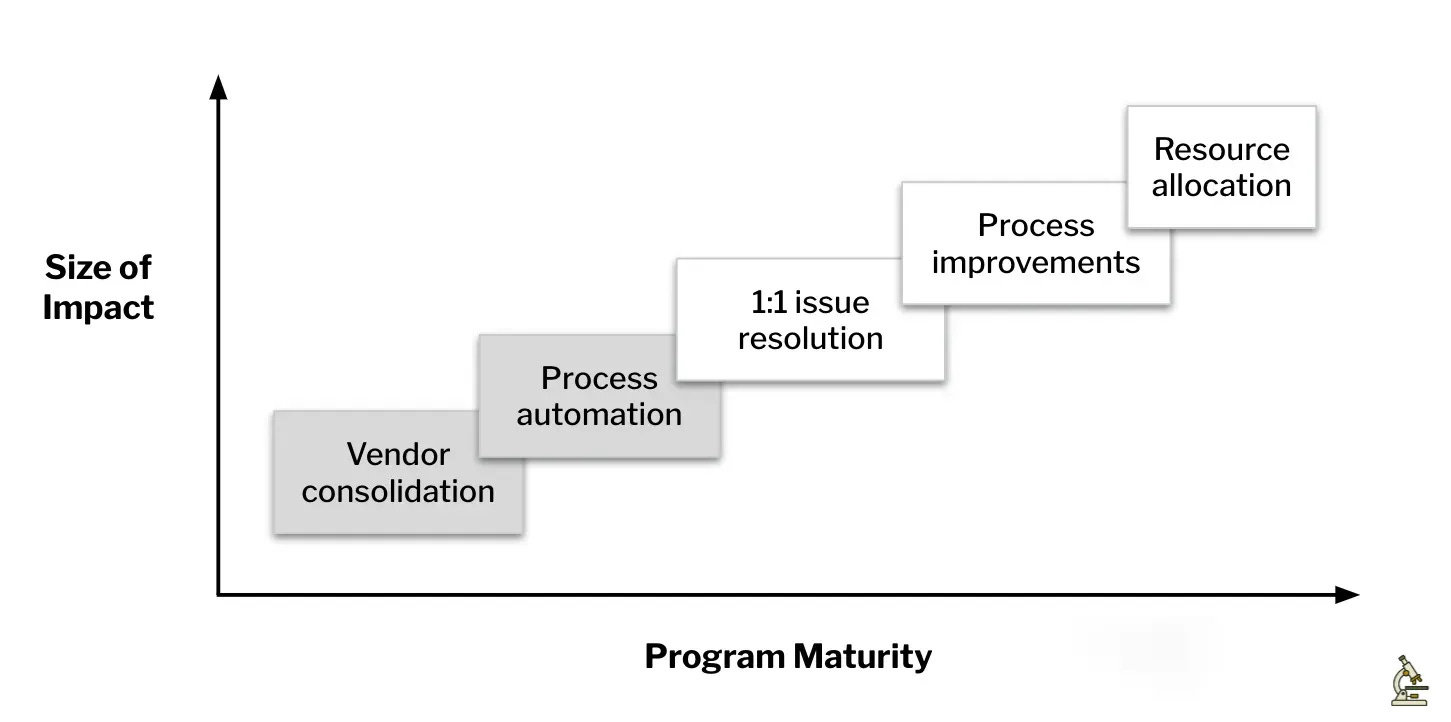

Here’s how I categorize actions:

Vendor consolidation: While often not the largest source of value, vendor consolidation can provide quick, easily quantified cost savings.

Process automation: Process automation makes people’s lives easier and the impact can be relatively easy to quantify.

1:1 issue resolution: Resolving customer issues can be a great way to influence customer spend.

Process improvements: Improving processes requires influence and resources but is a great way to scale the impact of your insights.

Resource allocation: As your program gains credibility, you can have a greater influence on how the company allocates resources at the highest level.

Place actions at the center of your efforts to understand the value created by your CX program. And if you haven’t driven meaningful actions yet, start there.

Recommendation #3: Run more experiments

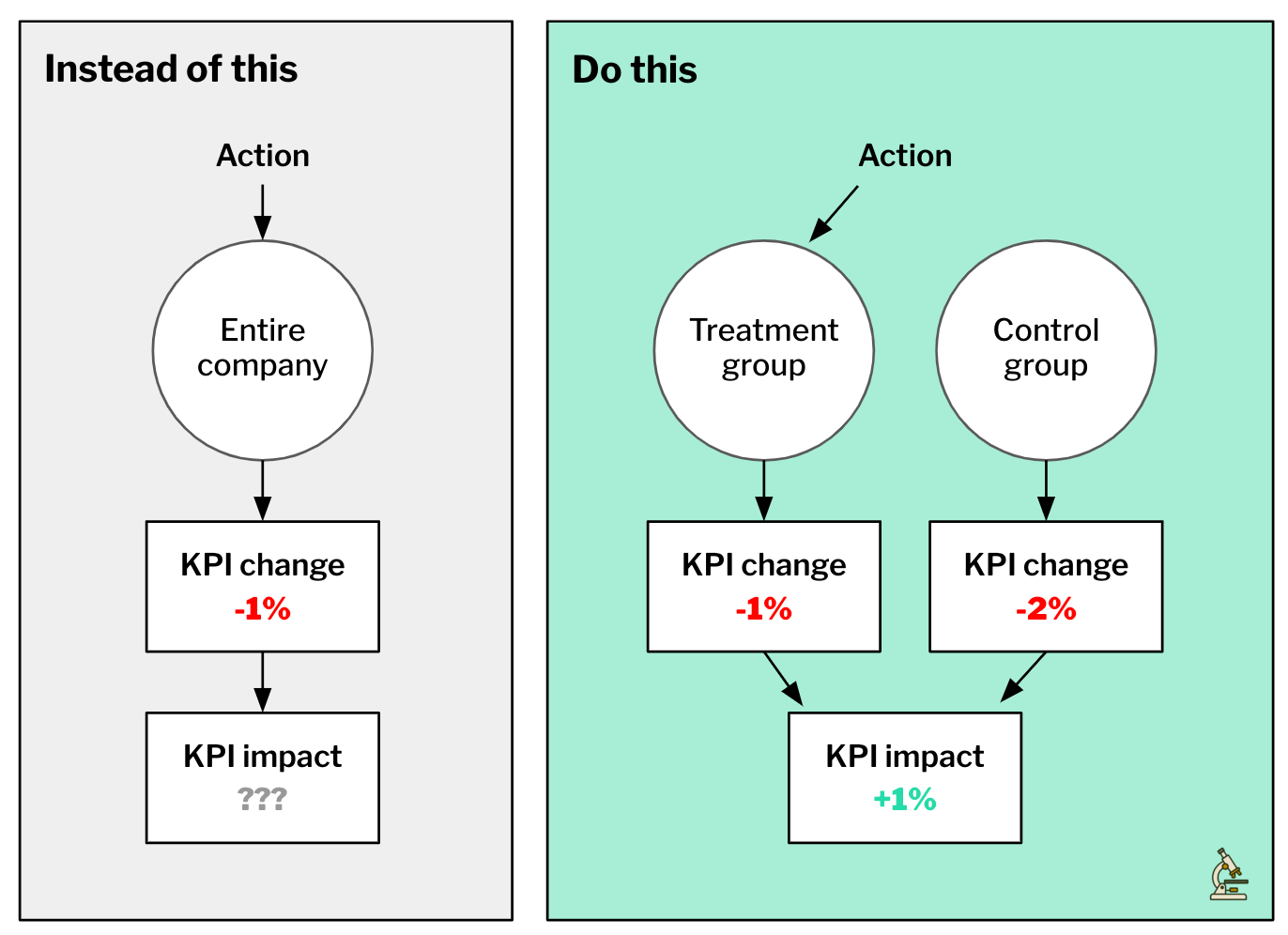

Questions like, "What impact has CX had on our business?" are causal questions, but CX teams typically try to answer with correlations. Consider the ladder of causation below16. CX teams are trying to answer rung 2 and rung 3 questions using rung 1 methods:

Associations are great for generating hypotheses and answering rung 1 questions like "How likely is ABC customer to churn?" But they aren’t sufficient for answering rung 2 and 3 questions like “Will this customer churn if we improve their experience?” or “What would have happened if we hadn’t intervened?”17

Experiments are a powerful but underused way for CX teams to climb the ladder of causation. Below are three myths that often discourage people from running experiments.

Myth #1: I can't run an experiment because I don't have formal experimentation training

Advanced techniques can improve the quality of your experiments and analysis but they aren't necessary to make a meaningful reduction in uncertainty18. Consider using the mnemonic PICO:

Problem: What are you solving for? This is likely your insight.

Intervention: What are you doing about it? This is your action.

Control: Who will you compare the treatment group to? For example, if you launch a pilot program, set aside a control group that is similar to the pilot group.

Outcome: What are the success metrics? To show business value, focus on metrics related to customer acquisition, spend, retention, and cost to serve.

Myth #2: I can't run an experiment because I won’t have enough observations

When people think of business experiments, they often imagine high-volume A/B tests run by large companies on their websites. For example, booking.com runs tens of thousands of experiments per year, many of which receive millions of observations19. They see those experiments and think, "No way."

Fortunately, experimentation isn’t all-or-nothing. Many people think they need to achieve a certain p-value for results to be useful. This thinking is a trap. Every observation you collect is a reduction in uncertainty. The time to make a decision is when it is not worth reducing uncertainty any further — not when you achieve some arbitrary level of statistical significance.

Myth #3: My business stakeholders wouldn't support my efforts to run an experiment

While the appetite for experimentation varies across organizations, running an experiment helps your stakeholders manage risk. By deploying a smaller scale version of your action, you generate evidence for whether it is or isn't a good investment before committing more resources.

“Instead of merely concentrating on trying to discern some signal from an inherently noisy set of observations, we should focus more on trying to understand and eliminate the noise. Come up with ingenious experiments to isolate what you are trying to measure. One such high-quality experiment is worth a hundred statistical tests.”20

Closing

In summary, I don’t think organizations should try to put a monetary amount on CX scores. Just because customer experience can impact business value doesn't mean that CX metrics are a good proxy for it. It is more reliable and defensible to focus on the impact that specific actions have on your outcomes of interest.

Thank you to the many people who have helped improve my thinking over the years. Luke Williams, Elizabeth ErkenBrack, Daniel McCarthy, Pete Fader, Judea Pearl, and Douglas Hubbard have been particularly impactful in shaping the ideas in this essay21.

To the reader, please share critiques!

Or customer satisfaction, customer effort score, etc. Further, while this essay is about CX, I make the same argument for employee experience metrics.

Some people argue that using satisfaction as a proxy for business value is OK because “any model is better than no model.” The issue with that argument is that we have a better model.

For example, The four causes of customer churn and what to do about them (Luke Williams, November 2020)

For example, Experience Management Leaders’ Stock Price Outperformed Peers Through COVID (XM Institute, July 2022) and Stock Returns on Customer Satisfaction Do Beat the Market: Gauging the Effect of a Marketing Intangible (Journal of Marketing, September 2016)

For example, Global Study: ROI of Customer Experience, 2023 (XM Institute, May 2023) and Satisfaction Strength and Intention to Purchase a New Product (Journal of Consumer Behavior, September 2012)

Poon, C. S. K., Koehler, D. J., & Buehler, R. (2014). On the psychology of self-prediction: Consideration of situational barriers to intended actions. Judgment and Decision Making. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1930297500005763

Mazursky, D., & Geva, A. (1989). Temporal decay in satisfaction–purchase intention relationship. Psychology & Marketing. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.4220060305

For example, The Impact of Customer Satisfaction and Relationship Quality on Customer Retention: A Critical Reassessment and Model Development (Psychology & Marketing, December 1997) and Satisfaction and repurchase behavior in a business-to-business setting: Investigating the moderating effect of manufacturer, company and demographic characteristics (Industrial Marketing Management, 2007)

Hirschman, A. O. (1970). Exit, voice, and loyalty: Responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states. Harvard University Press.

Fader, P., & McCarthy, D. (2020, January 15). How to value a company by analyzing its customers. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2020/01/how-to-value-a-company-by-analyzing-its-customers

For more on this topic, check out Balancing value to your customers, employees, and business (Topher Mitchell & Elizabeth ErkenBrack)

I suspect most CX professionals want to spend more time generating insights and driving action and less time educating their co-workers about their metrics.

Template: Value Chain Framework (Topher Mitchell, May 2024)

“Negative” actions count too; e.g. stopping a bad process or deciding not to undertake an initiative

Pearl, J., & Mackenzie, D. (2018). The book of why: The new science of cause and effect. Basic Books. Drawing by Maayan Harel.

Remember that you aren’t trying to persuade the people who want to believe you — you’re trying to persuade the people who are skeptical or who actively don’t want to.

Though, if there are experimentation experts within your company, ask for help!

Thomke, S. (2020, March 1). Building a culture of experimentation. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2020/03/building-a-culture-of-experimentation

Clayton, A. (2021). Bernoulli’s fallacy: Statistical illogic and the crisis of modern science. Columbia University Press.

These ideas were originally published as a 7-part series in 2023, now consolidated and improved