3 must-answer questions for every resource request

Where to focus to help decision-makers feel confident making an investment

Anyone who has tried to drive significant change within an organization knows how hard it can be to get the resources they need (budget, headcount, etc.). It’s nearly impossible when times are tough, and it’s hard even when times are good.

To make matters worse, it can be maddening to be denied your request when you thought your business case checked all the boxes.

I’ve been through the resource request process hundreds of times. I believe there are 3 fundamental, under-appreciated questions that any requestor needs to answer to maximize their chances.

Let’s start from the perspective of the decision maker. This person is a steward of the organization’s resources, responsible for allocating them in the best way they can. For corporations, this usually means driving cash flow.

These leaders often face dozens if not hundreds of requests per budget cycle, most of which are pitched as “mission critical.” They can’t get into the details of every request and have to make quick decisions, most of which are rejections.

The 3 questions

Whether they say it or not, these decision makers want you to answer the following1:

Which metrics will this impact?

By how much?

Why should I believe you?

The questions are simple, but that doesn’t make them easy — especially if you aren’t prepared2. Failure to answer hurts your chances, maybe even your reputation.

Some might say, “There is so much more to a business case! What about the ROI estimates, charts, math3, risk analysis, etc.??” If they help you answer the three questions, great. If not, they are a distraction.

So how do we answer them? Let’s look at each one:

1. Which metrics will this impact?

I look for a small number of metrics (usually, 1-3) that closely align to the decision-maker’s priorities and that are relevant for the initiative

To answer the first question, start with the problem you are trying to solve. What makes this problem painful? What happens as a result of it? What would happen if it were no longer an issue? Keep digging. If it’s a legitimate problem, you’ll eventually get to specific business metrics4.

Business metrics are KPIs that have a direct connection to what the business values — cash flow5. If your metrics are tied to customer acquisition, customer spend, customer retention, or cost to serve, you’re on the right track6. For example:

Customer churn rate

Lost productivity (e.g. hours per week)

Cart abandonment rate

Total vendor spend

Support call volume

If you’re having trouble making the connection between your proposed initiative and business metrics, ask around. People affected by a problem often have a perspective on what outcome it is affecting. You can also ask your favorite LLM:

“Our organization is currently struggling with XYZ. What business metrics is this problem likely affecting? Please give me a list and an explanation of each metric.”

If you still can’t make the connection, maybe the problem isn’t worth your time. Better to find out on your own than when you’re in front of the decision maker.

2. By how much?

I usually want to see an improvement range associated with the metric of interest (e.g. 2-5% reduction, 700-1000 hours saved, 10-20 customers retained)

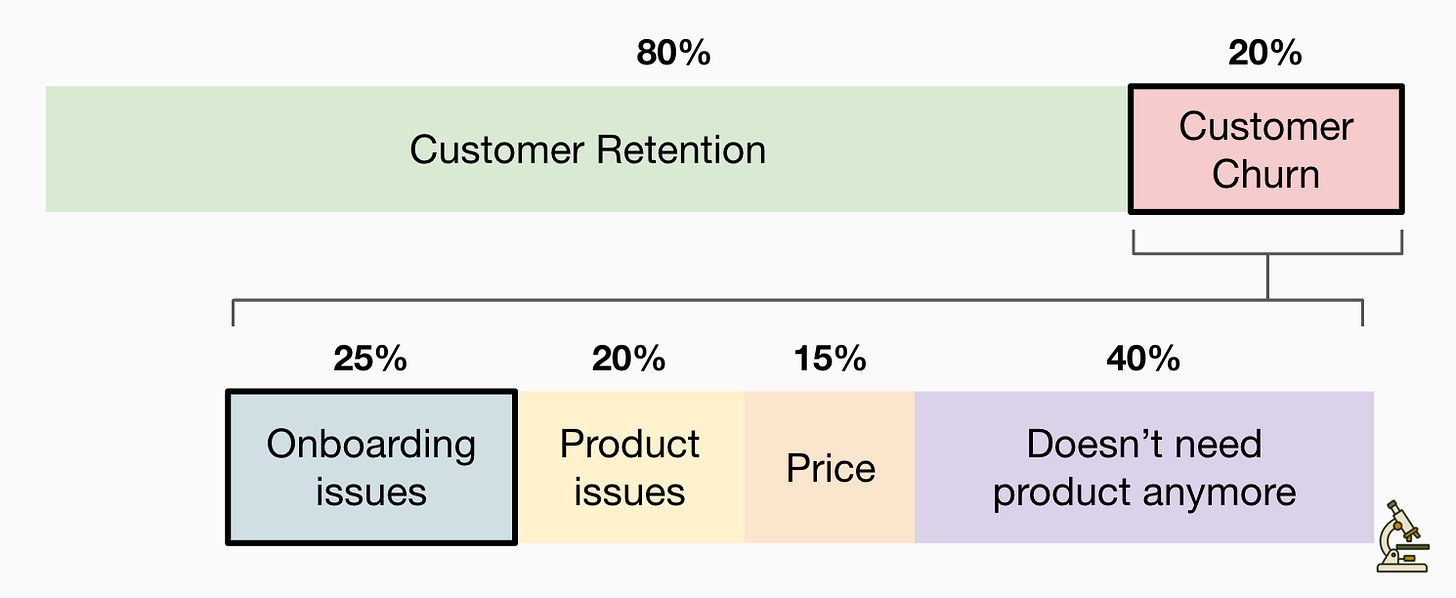

I like to approach this question by breaking the down the negative outcome into its addressable and non-addressable components. Imagine we want to fix an issue with our customer onboarding experience, which we think is contributing to customer churn. Here’s how we might break down customer churn:

As you go through this, consider that:

These are estimates so use ranges to account for your uncertainty.

Bigger improvement estimates do not mean better. Defensible is better.

Sometimes you have the perfect fix but usually you don’t. Be realistic about how much you can actually address.

This lets you say something like the following to the decision maker: “We think we’re leaving $x on the table every year due to this specific, addressable issue.” And it would be great if they responded with something like, “Hmm, I had no idea it was that much.”

3. Why should I believe you?

I want to see the work behind the answer to the prior question, including quantitative and qualitative evidence

Decision makers need assurances that value will be delivered. They need a good reason to rely on your estimates from question #2 (By how much?). And the burden of proof largely depends on the size and risk of your request, with bigger, riskier requests requiring stronger evidence.

But, collecting evidence costs you time and resources. So reduce your uncertainty until it isn’t worth reducing it further. This means starting with lower cost measurements and moving to higher cost measurements. Keep going until the incremental benefits no longer exceed the incremental costs.

Here are the 5 methods I use to reduce uncertainty, in order from lower to higher cost:

Provide your initial estimate range: Even wide ranges are helpful

Look for existing research: Internal studies or external benchmarks / reports

Ask experts: People close to the issue or domain experts (internal or external)

Find, clean, and analyze existing data: First party data can be great evidence

Collect additional observations: New survey research or an experiment

Also consider that the decision maker doesn’t just need to believe your estimates. They need to believe YOU. Your track record, reputation, and level of skin in the game play an important role. If you don’t have these things, you may need others who do to vouch for the investment7.

In conclusion

You can summarize the justification for your request with a simple madlib:

“We expect this initiative to impact [outcome metric] by [estimated range]. Here’s why we believe this…”

This doesn’t guarantee you will get what you want. If your proposed investment isn’t the best use of resources, it shouldn’t be funded. And even if it is the best use of resources, you are still subject to the preferences, priorities, methods, and whims of the decision maker. Control the controllable. Focus on what matters. Maximize your chances of a positive outcome8.

Honorable mentions: How will this investment deliver these results better than other options? How can I hold you accountable to these targets? Who will be responsible for execution? Where could it go wrong?

A common mistake is believing you can build your business case once someone asks for it. You can get away with that sometimes, but I would rather not risk it. CFOs tend to be critical of those who didn’t do their homework. You aren’t guaranteed a second chance.

It’s not about the math. Decision makers usually don’t need you to do their math for them.

Some investments may be “exploratory” in the sense that there aren’t well-defined outcome metrics. This can help drive innovation without needing to wait until the business outcome is fully understood. Otherwise, an ambiguous payoff usually doesn’t cut it.

Sometime people argue that certain benefits are just “strategic” and not quantifiable. Well, how is the decision maker supposed to believe they are real? I talk about the issues with “strategic” value in this article.

If you work for a non-business (e.g. a local government), your organization might value different outcomes than cash flow (e.g. participation rate in state programs). Align with what your organization values.

The decision maker’s first phone call will probably be to the person with the most skin in the game (i.e. the person who stands to gain or lose the most based on the performance of the investment). It’s really helpful if this person defends the estimated benefits.

Going through this process can also help you improve your plan for execution.